The Last of the Magicians

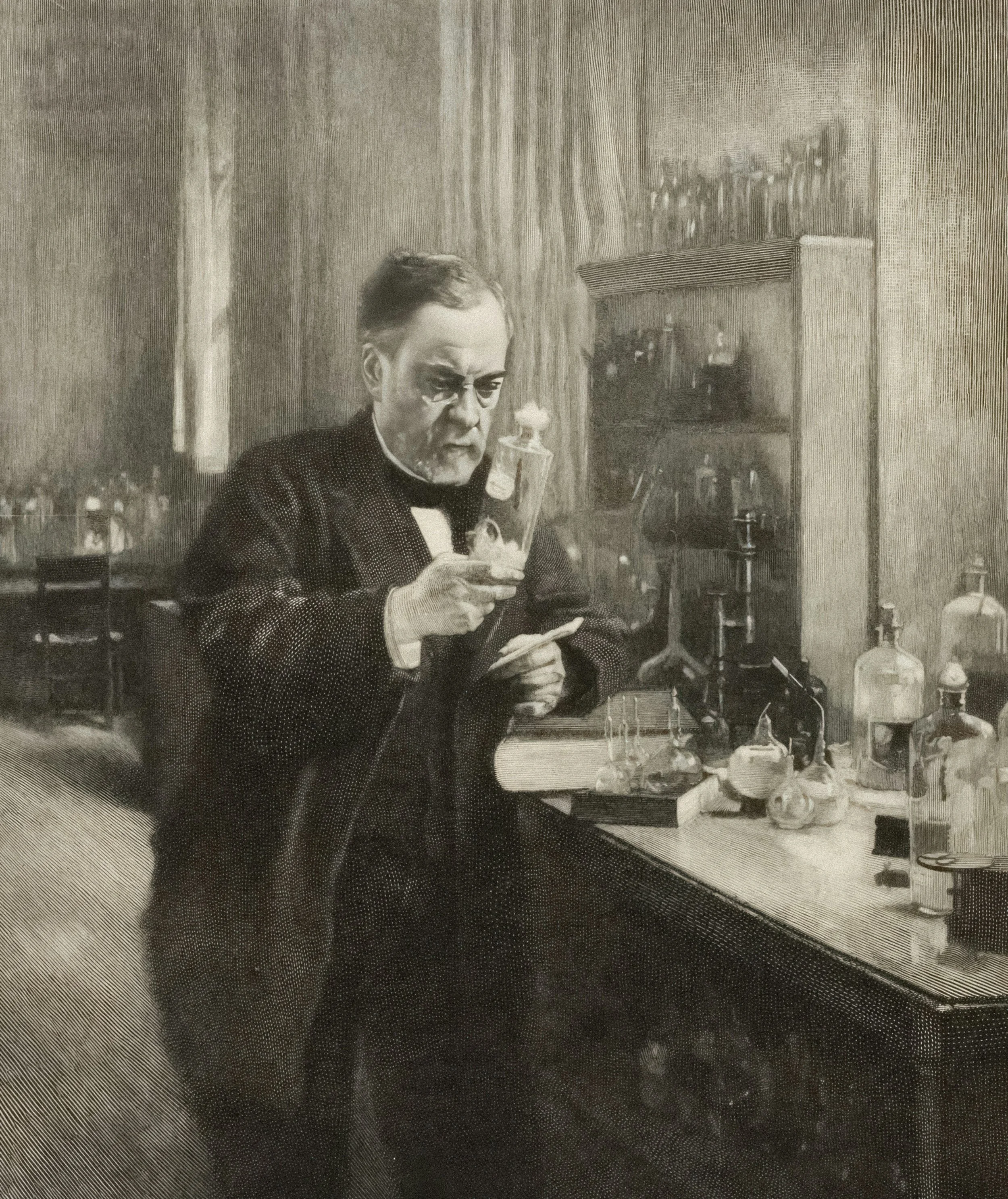

The Last of the Magicians

Ben Creasey.

Science has often been presented as an austere and purely rational enterprise: a discipline that is maintained through rigid method, measurement, and the gradual accumulation of facts. Likely, the term ‘scientist’ conjures up images of a white lab coat, protective goggles and a pristine laboratory. According to this particular image, the process of scientific discovery and understanding appears to emerge, not from passions or speculative philosophies, but from an objective detachment and cold realism that views the world simply as an object to be observed and investigated.

Curiously, this image begins to fracture when more closely investigating the very figures that modern science is built upon. Many of the most notable pioneers of the field such as Newton, Tesla and Edison, were motivated by distinct beliefs and an enduring metaphysical curiosity that would struggle to identify with the cold rational ideals that science is often understood as promoting. Rather than undermining science however, the tension between the popular image of science and the reality of its proponents underscores the fact that scientific progress remains a product that is of deeply human origin in its passion and imagination.

Science and the Holy Trinity

In 1946 the renowned economist, John Maynard Keynes, having purchased an extensive archive of his writings, gave a remarkable lecture on the work of Isaac Newton. In line with the popular understanding of the nature of scientific endeavour, Keynes began by remarking on Newton's incredible reputation as a ‘rationalist, one who taught us to think on the lines of cold untinctured reason’. This being a fairly unanimous perspective for the time, it was a great surprise that Keynes, having thoroughly investigated the breadth of Newton’s work firmly followed this up with ‘I do not see him in this light’. Newton’s archived work illuminated a very different image of him than the conventional, revealing his disbelief in the Holy Trinity, his intense apocalyptic interest, believing that the world would end by 2060, and beyond all other curiosities, alchemy. Newton’s writings revealed, in fact, that he wrote far more upon alchemy than he ever wrote upon the subject of mathematics. The library of Newton further revealed that he had been in contact with many other prominent figures who shared his alchemical interest. Robert Boyle, an early founder of the Royal Society of London and an individual often referred to as the first of the modern chemists, passionately pursued alchemy believing in the eventual discovery of the fabled philosopher’s stone. Also mentioned is the Flemish physician Jan Baptiste Van Helmont, referred to as the father of pneumatic chemistry, also credited with being the first to coin the term ‘gas’, was himself a disciple of the German mystic and alchemist Paracelsus.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Keynes' lecture is not the revelation of the mystical and irrational desires at the heart of the most prominent figure of modern science, but rather the apparently deliberate concealment of the fact. Keynes argued that the scope and character of Newton and his work had been ‘hushed up’ or at least ‘minimized by nearly all those who had inspected them’ in order to preserve the rational image of one of science's foremost proponents.

The desire to ‘sanitise’ the character and beliefs of key scientific figures stems from the context in which science established itself as an authority. In the 16th and 17th centuries, modern science emerged in a period where the world was largely understood theologically as the Church held sovereign control over institutions. In order to distinguish itself from religious authority, science was portrayed as a system based purely upon observation and reason. In this sense, the origin of our popular image came about as a defensive strategy, not as a fundamental necessity of science. It was this original defensive measure that was increasingly built upon. To establish universal authority, cold rationality was upheld as it promised neutrality, repeatability and universalisability. By contrast, passion, belief and imagination were understood to be subjective and socially and culturally determined and therefore not aimed toward a universal truth. This resulted in a distinct fear that overt ties to passions or beliefs that lay outside of science may bring about cracks in the universal authority it had sought to gain, as is shown in the case of Newton.

Werner Heisenberg emphasises in his Physics and Philosophy, that every advancement ‘carries with it the spirit by which it was created’. Heisenberg here was concerned more specifically with the developments of nuclear physics, but this axiom raises a significant point in regard to the scientific enterprise as a whole. The illumination of the case of Newton reveals an anxiety that underpins the image of science as a detached and rational investigation and moreover an anxiety that still operates defensively, in the spirit in which it was formed. This anxiety is shown through attempts to mould the most prominent scientists and inventors into the archetypal image that best maintains the legitimacy and universal authority of the field. This image is at odds most consistently with the words of the very scientists who are most closely associated with it. Nobel Prize winning physicist Max Planck, the origin of quantum physics, described the necessity of spirituality in scientific endeavours: “Both religion and science require a belief in God. For believers, God is in the beginning; for physicists, He is at the end of all considerations.”

The image of ‘the scientist’

Planck’s words present an image of science that will always retain a point it cannot quite reach or fully explain and yet it is also to that point that its final curiosity is aimed. Albert Einstein provides a further justification for the intimate relation between the spiritual and the scientific: “Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.

Einstein often wrote of a ‘rapturous’ and ‘divine’ amazement at the investigation of the universe since it was only through religious language that he could best convey the incredible wonder which it presented to him. It was the American Astronomer Carl Sagan however who perhaps refined this sentiment to its most significant aspect: “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality”

Sagan emphasises the fact that the spiritual and the scientific are not contradictory but are rather two necessities that complement the other. The beauty and workings of the universe seen in science can take such a passionate hold of the individual scientist that, like Einstein, they only have recourse to the poetic and abstract to hint at its depth.

Keynes’, in his lecture, posits that Newton was not the first of the modern scientists, as had often been claimed, but rather the ‘last of the magicians’. Keynes emphasised that he thought Newton no less great for this fact.

Ben read Philosophy at the University of Winchester and is a beloved CATALYST work experience colleague. You can read more of his work on his Substack: Ben's Substack | Ben Creasey | Substack